Every Nov 1, I interact in an uncommon ritual. As quickly because the Halloween decorations are down, I unleash a turkey on Los Angeles, the United States – and the world.

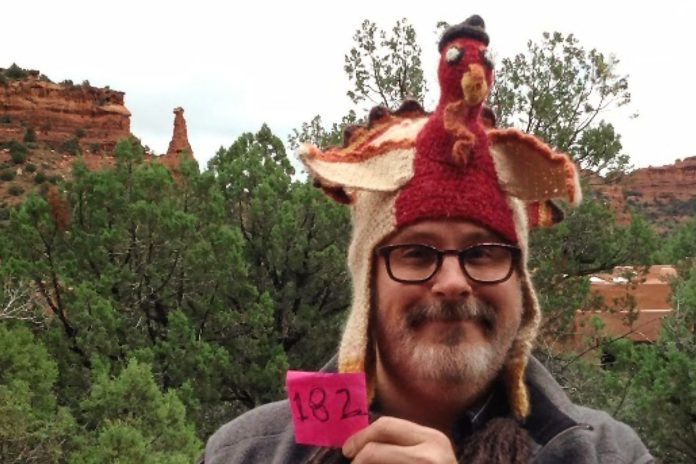

Not a stay chicken but a gravy-coloured knit chullo (a.okay.a. an Andean ear-flap hat), topped with a cartoonish-looking, Pilgrim-hat-wearing turkey, with flappy knit wings that bounce with my each step.

It’s a fully ridiculous piece of headgear that I make a level of carrying out within the wild – driving to work, working errands, that type of factor – as typically as attainable till the day after Thanksgiving.

I began carrying it seven years in the past to cheer up my father as he battled the metastatic melanoma that may declare his life not fairly two weeks after Thanksgiving.

Despite the sombre backstory, sporting the goofy lid is definitely a joyful homage to my dad, whose sense of humour was well-known to those that frequented our family’s Vermont nation retailer.

He appeared to have the ability to join meaningfully with anybody who walked by means of the door, from toddlers to their retiree great-grandparents.

Wearing the turkey hat round LA someway appears to forge a related connection – starting from the hardly perceptible nod of acknowledgement from parking-lot attendants to “Hey, turkey man!” yelled from behind the counter of a Grand Central Market taqueria.

From afar, I often reply with a smile or a thumbs-up. In nearer proximity, I’ll lean in and whisper in a conspiratorial tone: “Did you discover the turkey on the hat is carrying a hat?”

I’ve all the time relished these interactions, but this yr, the seventh season I’ve plopped the poultry on my pate and waddled out into the world like a punchline with no joke, these fleeting moments of feeling seen are much more significant, a technique to actually, safely join with strangers in an atmosphere the place social distancing is the norm and smiles are obscured by face masks.

It’s like a hug in a hat, a means of spreading vacation cheer within the run-up to a collection of year-end holidays. That realisation made me assume fondly again to the circumstances that gave rise to the annual carrying of the turkey lid – and my dad’s function in it.

I impulsively purchased the Peruvian-made hat in Sedona, Arizona, 4 days earlier than Thanksgiving in 2013.

I was taken partly by its comical look – eyes knit into a everlasting expression of shock, a black brimmed hat perched precariously upon its head, a knit wattle unfurling from slightly below its knit beak and a ridged crown of autumn-hued tail feathers splayed out behind like peacock plumage.

As somebody whose private plumage had lengthy flown the coop, I additionally knew the knit cap with its dangling pom-pommed earflaps would offer a measure of insulation towards Sedona’s surprisingly cool (not less than at the moment of yr) local weather.

While the hat actually turned heads that first Thanksgiving, it wasn’t imbued with a lot that means. That got here the following November, after I received the decision from my family again East that I was wanted to assist take my dad, who had been identified with melanoma, from Vermont to Boston for a seek the advice of on the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

The turkey hat, which had simply been sprung from storage together with the opposite Thanksgiving accoutrements (turkey-themed cocktail napkins and a DVD of Planes, Trains and Automobiles), discovered its means into my unexpectedly packed bag, and off I went.

It was with me when what was imagined to be a five-hour drive to Boston and again metastasised into an emergency gauntlet of MRIs, physician visits and my father’s completely sudden two-week keep at Brigham & Women’s Hospital.

It was throughout this time that the magic of the turkey hat slowly revealed itself to me. I wore it into and out of the hospital day by day of these darkish two weeks, figuring out it could deliver a smile to my dad’s face. What I did not anticipate was the way it equally affected the hospital workers and different sufferers I’d cross within the hallways or see within the elevators.

My first “Hey, turkey man!” call-out got here simply a few days in after I walked by a hospital-gowned affected person wheeling his IV stand down the hallway for a little train. I’d cross him within the hallway a half-dozen extra instances on that journey.

On every event, he’d break into a broad smile and flash me a thumbs-up with the hand that wasn’t steadying his transportable IV rig. Some days I’d plop it on my father’s head as he was being wheeled down into the bowels of the hospital for one of many countless rounds of imaging.

On these days, each he and the hospital staffer accompanying him would return grinning ear to ear. No one in our family would take into account these two weeks something but a terrifying emotional curler coaster, but rattling if cramming that turkey-shaped pile of hand-knit acrylic atop my head did not make it really feel simply a tiny bit much less bleak for these of us coming to phrases with my father’s quickly approaching loss of life.

Although I’d actually seen loads of strangers react to the hat, I was so centered on attempting to repair my frail and failing father that I did not assume far more about it – till the day I left it behind after we wheeled my dad down for yet one more spherical of X-rays.

“Where’s the turkey hat?” requested an X-ray technician whom I did not assume I’d ever seen earlier than. I responded with a shrug.

“You ought to maintain carrying it as a result of it has been cheering folks up round right here,” he stated.

Taking that recommendation to coronary heart, as soon as we received again to the room I grabbed that turkey hat by the earflaps and tugged it onto my head, the place it could stay (but for my day by day bathe) throughout the time I was in Boston.

I was carrying it after I kissed my father on the brow for what turned out to be the final time. I wore it whereas my sister drove me to the airport, each of us sobbing uncontrollably, to wing my means again to LA simply days earlier than Thanksgiving. And I wore it as I concurrently FaceTimed my family again dwelling and grief-cooked turkey and all of the trimmings right here.

When my father died – at dwelling, surrounded by family – on Dec 10, 2014, I was devastated, but I was additionally grateful that I’d had the possibility to spend time with him and make him giggle when there was valuable little to giggle about.

The subsequent yr, when Nov 1 rolled round and I opened the field of Thanksgiving decorations, the very first thing my eyes landed on was the turkey hat. I grabbed it by the pom-poms and tugged it onto my head, and the recollections of the yr earlier than got here flooding again.

I wasn’t utterly certain, that first yr, that I wished to put on the hat out into the world once more, frightened it’d someway tarnish the recollections or mitigate the magic.

Now, seven years on, I realise these had been pointless worries. Every time I trot that turkey hat out, I see my father’s smile within the smiles of strangers.

I really feel his eyes take within the spectacle of me lumbering by means of a Rite Aid car parking zone with my knitwear-shrouded noggin held excessive, and I hear his distinct voice within the exclamations of “turkey man”.

This time of yr is aggravating for everybody, and for individuals who have misplaced family members, it can be painful. So, if I can alleviate a tiny little bit of that ache – even momentarily – by wandering round LA wanting like a one-man Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade, it is properly well worth the effort. – Los Angeles Times/Tribune News Service